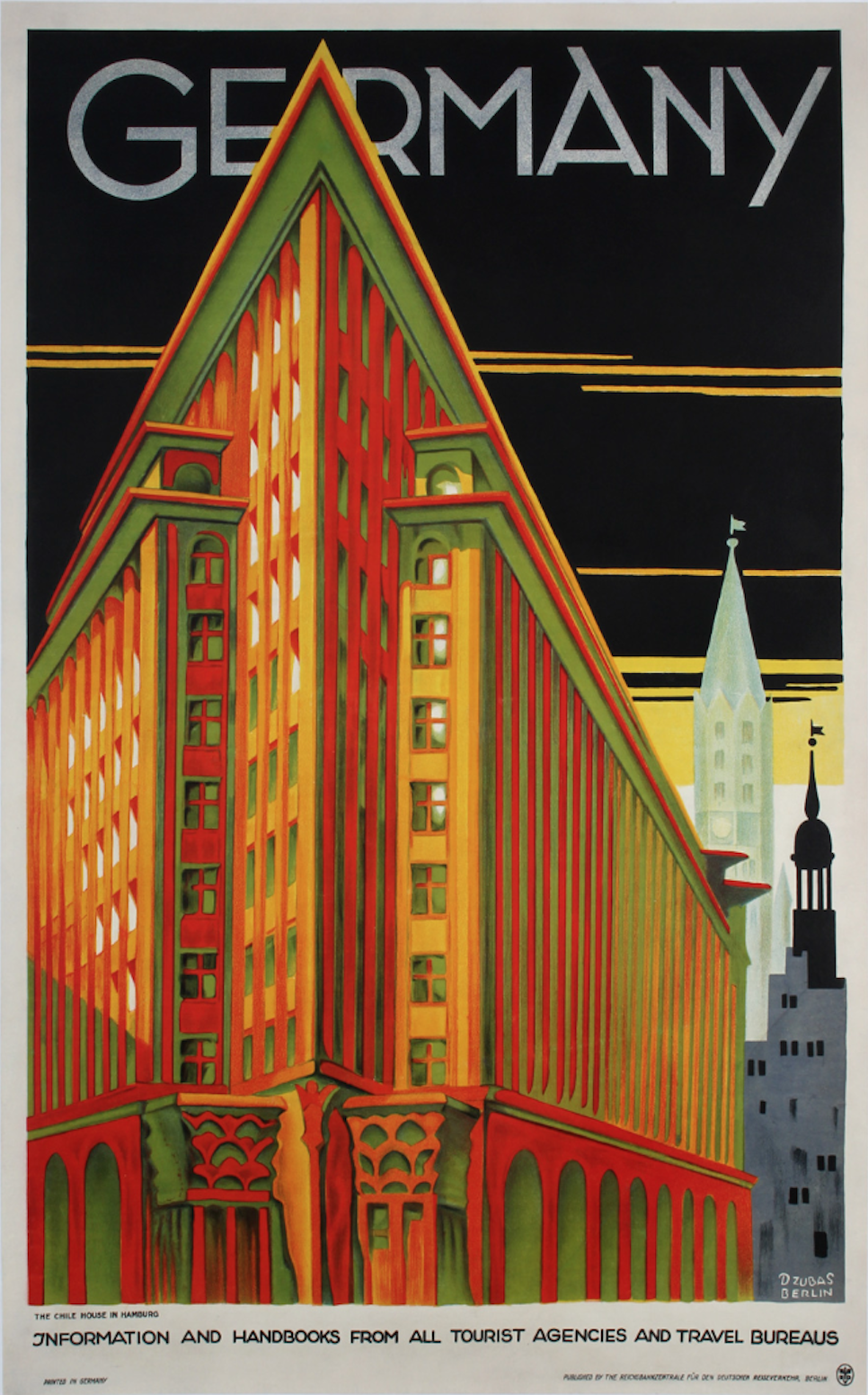

I’m sure you will know the Chilehaus – that ship‑like giant, built of brick, jutting out in Hamburg’s Kontorhaus district. It’s a landmark of Northern German Brick Expressionism, designed by Fritz Höger and completed in the early 1920s [see an image down below]. But little is known that this iconic landmark set the stage for another brilliant mind: Ossip Klarwein (1893–1970).

In 1927, Höger hired Klarwein as chief architect. Until 1933—a pivotal year in German history—Klarwein helped shape the look and ambition of Höger’s office. His influence reached beyond Hamburg, most famously with a Berlin church at Hohenzollernplatz, whose bold silhouette earned it the nickname “God’s power station.”

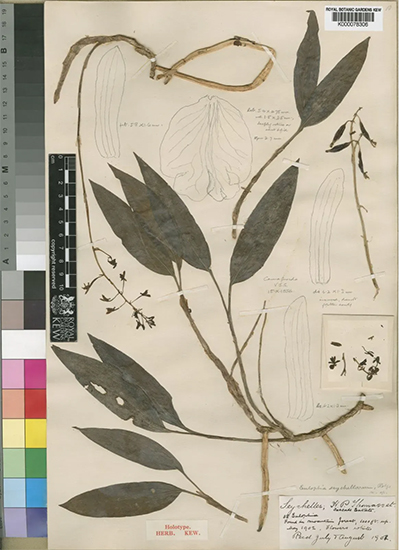

Ossip Klarwein was closely connected to Hamburg and the building styles of the North Sea region. When the Nazis took over in 1933, he was forced to leave for Haifa, Palestine. He first scrambled to gain a foothold, but by 1945, he was appointed to design key public buildings, thereby coining a Modernist style that would shape many later structures.

Many, only very recently excavated visual and written documents have been assembled to an exhibition of international collaboration: a collage of Klarwein’s life and work. Complemented by large-format pictures by the Israeli photographer Eli Singalovski (*1984). After its premiere in Berlin in October 2025, it is now showing at the Ernst Barlach Haus, as one of over forty contributions to The Jewish Cultural Heritage Days, 2025.

This, however, is only half of the “story” –

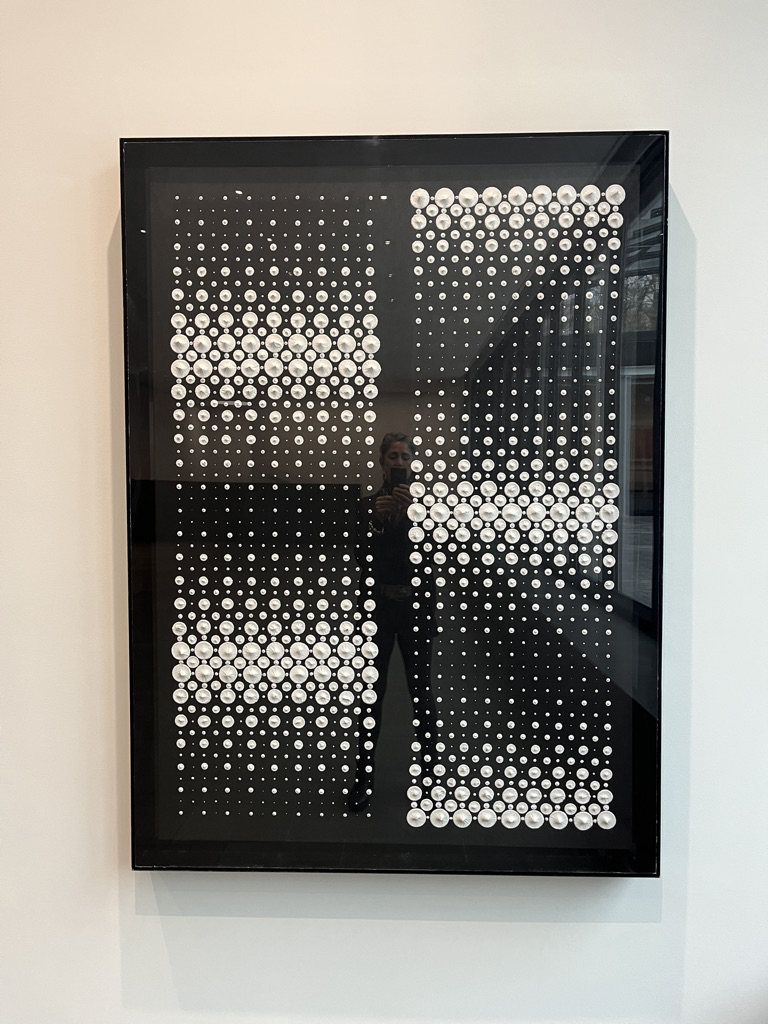

The Barlach Haus with its white, rather modest façade, does not immediately suggest that it can comfortably host two exhibitions at once – and yet it does. In the other half of the museum it feels like stepping into a very different universe: one of vibrating colour fields, serial structures and optical surprises. Here the atmosphere shifts towards Op Art – a movement many have heard of, but fewer could confidently explain, which is exactly what we will be exploring during the second half of our visit.

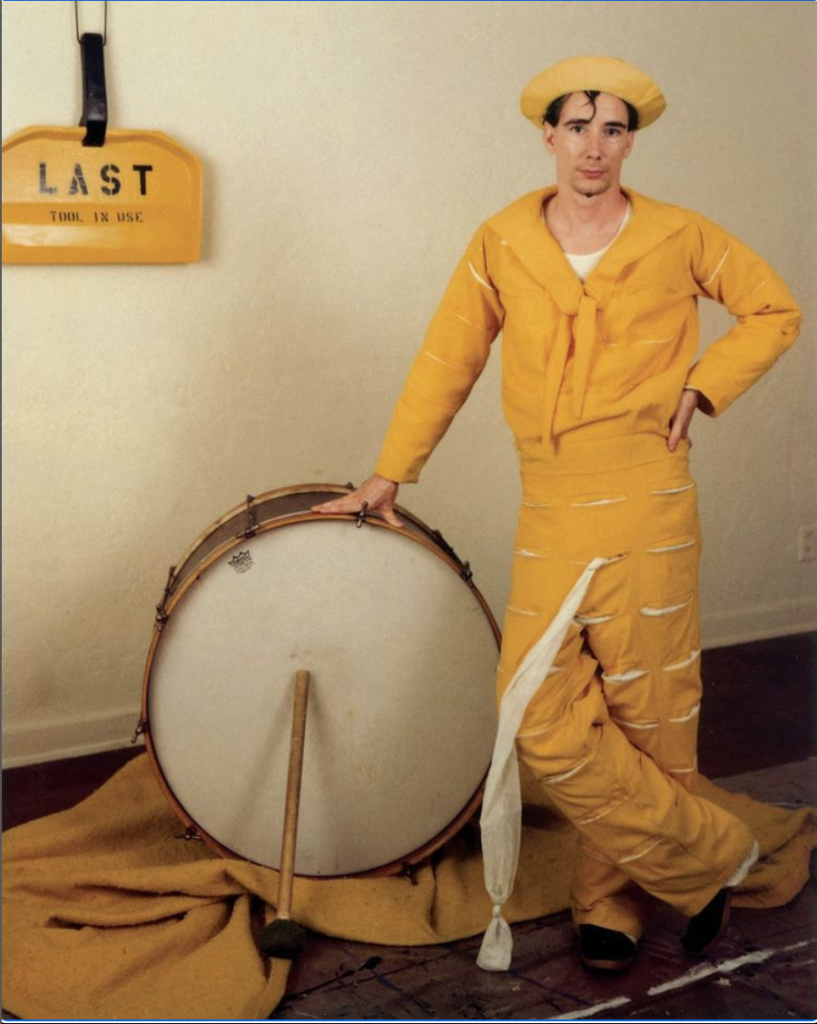

At the heart of this second “chapter” is Brazilian‑born artist Almir Mavignier (1925–2018), who had a deep and lasting connection to Hamburg. Mavignier is recognised as an important representative of Concrete Art and Op Art, who taught for 25 years as a professor at the HfbK, influencing generations of students. His artistic path began early in Brazil, where he worked simultaneously as painter, graphic artist and teacher.

An especially formative period was his work leading an art studio in a psychiatric clinic, where he experienced first‑hand how powerful simple forms and colours can be. Mavignier’s international breakthrough came after he moved to Paris and later to Ulm, where close contact with artists and thinkers such as Max Bill and Josef Albers sharpened his interest in systematic colour experiments and serial structures.

Instead of telling stories with figures or landscapes, Op and Concrete Art work with perception itself: grids, dots, lines and pure color are arranged so precisely that your eyes begin to do the “moving” for you. Standing in front of these works, you may notice patterns that seem to shimmer, tilt or pulse, even though the canvas is perfectly still. The longer you look, the more your own vision becomes part of the artwork.

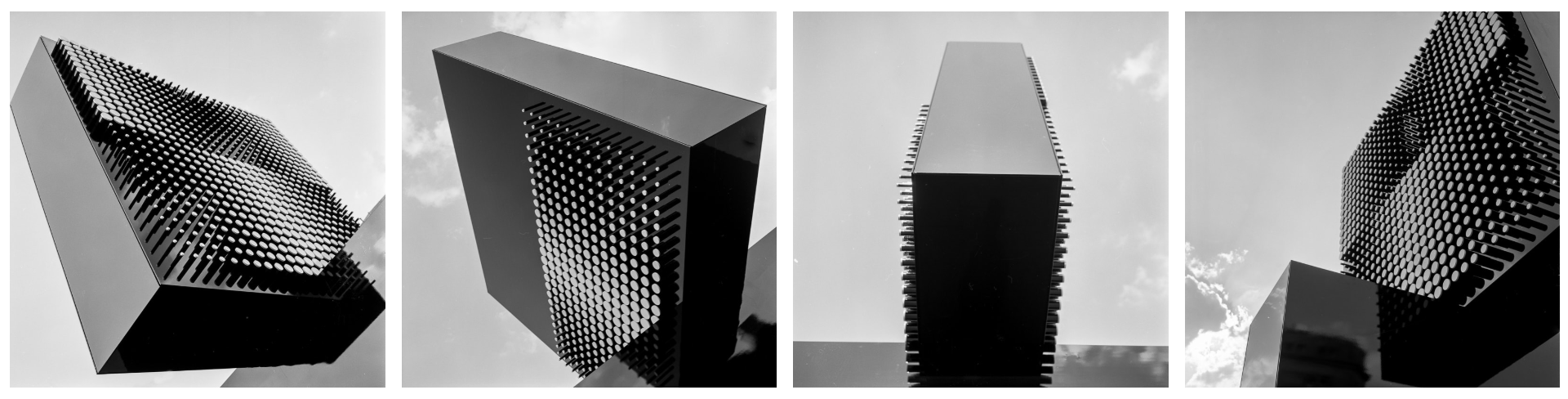

If you are in Hamburg, Germany then you may have even unknowingly walked past one of his few large outdoor sculptures titled convex concave and convex that was installed in 1971 at the Kirchenallee, Hamburg Hauptbahnhof. The complicated process of assembling the over six metres tall, black and white sculpture is documented on the official Mavignier website, run by his artist-son, Delmar Mavignier. It includes a full-length interview with the Almir Mavignier and shows many detailed, contemporary photographs by Carlos Struwe.

In the context of the Klarwein exhibition, Mavignier’s works add a rich counterpoint: while Klarwein builds with concrete and space, Mavignier builds with colour and perception – but both with the principle of organising spaces with repetitive patterns. Let’s explore these two remarkable modernists at Ernst Barlach Haus in Hamburg by booking tickets for my next tour here: