Art saved my life. Art was the place that made me want to educate myself. When I became an artist, it was where the most interesting thinkers were.

—Mike Kelley

I seem to encounter certain artists’ works at sometimes random but also symbolic moments, like that of the contemporary American artist Mike Kelley. This afternoon I was strolling down Hillhurst Avenue in Los Feliz, and virtually bumped into a large mural depicting him. I immediately recognized his face and stood there for a couple of moments to take in the large double portrait, the zig-zag patterns, the black and white areole, bright colours, and flying teddy bears. I thought back to when I had first seen his work, which hadn’t been in L.A. It was years ago, on one of my outings to the Galerie der Gegenwart (gallery of contemporary art) in Hamburg, Germany.

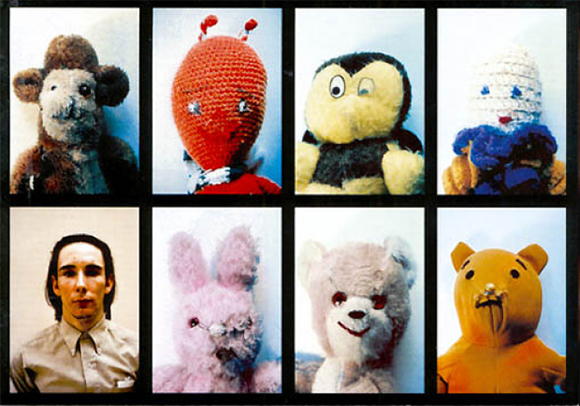

I had leisurely walked into one of the large gallery spaces and found myself transfixed by eight very unusual portrait photographs. Individually depicted were seven cuddly toys. Their stitched-on fabric or glass button eyes, some lopsided or missing, were staring at me with such resolve as if most desperately wanting to capture my attention. The eighth photograph is of a stern-looking young man with slicked back black hair, who I assumed, is the artist himself. The portraits are all displayed in a very simple frame and hung as a group in two rows of four. Despite the cool ambiance of an art gallery, and the innocence of the objects, they look like mug shots.

But wait, mug shots of an adult and children’s toys?

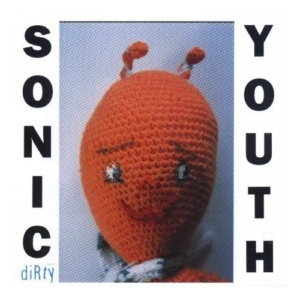

That was in the mid-nineties. I was a junior student of art history and discovered Mike Kelley’s artwork for the first time. It had immediately clicked. I didn’t know anything about his background, but I couldn’t help thinking about these strange mug shots from time to time. Maybe because they had also already found their way into music culture after Kelley created the artwork for Sonic Youth’s 1992 album Dirty, using Ant-Man’s “portrait” on the album cover.

Kelley was very connected to the LA art scene, which saw, starting in the 1990’s a very palpable period of growth and resurgence. He had initially studied under teachers like John Baldessari and Laurie Anderson at CalArts, where he earned a Master of Fine Arts. In addition to being a renowned visual artist, Kelley was also a musician, and before going to CalArts, a founding member of the proto-punk Detroit band Destroy All Monsters, who earned a cult following with their experimental performance art. Writing in The New York Times, in 2012, Holland Cotter described the artist as “one of the most influential American artists of the past quarter century and a pungent commentator on American class, popular culture and youthful rebellion.”

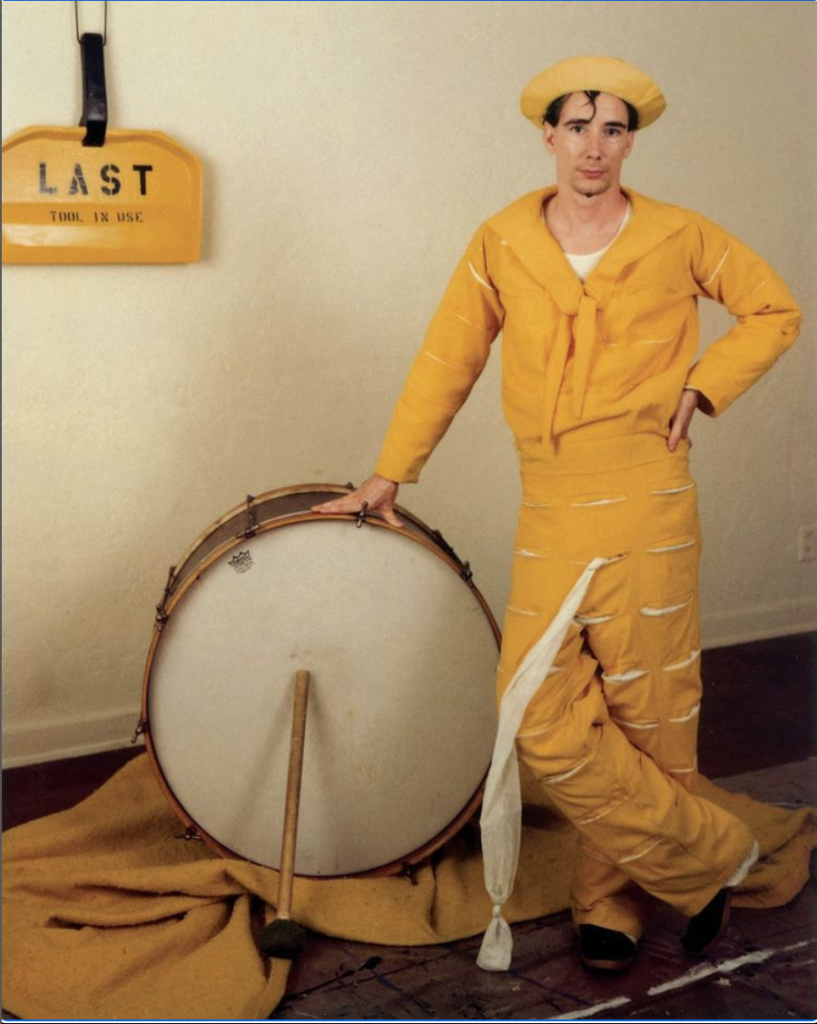

The following photograph must have served as a template for the mural above. It depicts Mike Kelley as The Banana Man: Written in 1981 and shot in 1982 while Kelley was teaching a performance/installation class at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design,1 The Banana Man was his first completed video work.

Stuffed Toys, Wax Candles, Afghans and Dried Corn

I had my second very intense encounter with Kelley almost two decades later. I had been living in Los Angeles for about six years and on one fairly uneventful, sunny morning, I was flicking through the L.A. Times when I read, that he had committed suicide. I was shocked in the way I often am when I’ve been assuming that life just flows along, that others will somehow always be around. He was only 57 and had by then established himself as an internationally renowned artist.

I dug a little deeper online, and read in further articles that only around four hours after confirmation of his death, an unofficial, makeshift memorial had started to appear in an abandoned carport at the top of Tipton Way, a few blocks from Kelley’s home in the Farley Building in Highland Park. Built from stuffed toys, wax candles, Afghans, and dried corn, mourners began replicating Kelley’s More Love Hours and Wages of Sin. These were two paired installations he had exhibited in The Whitney’s 1989 Biennial. I also learned that The Mike Kelley Foundation was organizing a memorial that was to be held at his studio in Eagle Rock/Highland Park on February 25, 2012.

I spontaneously decided to go. So on one of these for Los Angeles, typical mild February evenings, I drove through dimly lit streets to Kelley’s former residence. I parked on a side street lined with old gnarly oak trees, spiked with well-kept 19th-century craftsman bungalows, typical for South Pasadena. Like many pockets of Los Angeles, it felt very insular and isolating. I walked up to the main road towards the building in which the memorial was taking place. Its concrete steps led up to a very triste-looking entrance where a handful of people stood, collectively nodding as if to acknowledge my arrival. I felt a slight wave of guilt wash over me for being curious in a weirdly voyeuristic way. I had never met this man and yet I was showing up at a memorial – like a grief tourist? But I was curious. Who was this artist really? What was his provocative art really about?

Like approximately another 100 people, I wandered around through this vast space, which had been, only days prior to his death, his studio. Plastic cup in hand, filled with cheap red wine, exploring a maze of small administrative-looking side-rooms, watching sometimes only for a few minutes films Kelley had created. The main space, his studio, where more art installations were displayed and further screenings took place, reminded me of a large airplane hangar [see more pictures below]. It was a solemn and strange event but I was glad to be able to participate in something…

Ant-Man, Teddy, Rabbit and – Mike Kelley…

Two years after his death, in 2014, the largest ever retrospective of Kelley’s work was shown at L.A.’s Geffen Contemporary, part of the Museum of Contemporary Art (Moca). An extensive catalog on Kelley was also published by Prestel. I was able to take a closer look at much more of his impressive oeuvre, including the Ant-Man, Teddy, and Rabbit ensemble, which was also on display.

What really struck me this time was the way they are sitting there: stiff and unhappy-looking, tatty creatures propped up to have their photograph taken. Their fur coat or croquet suit is dirty, worn, and faded, limbs are limp, and they sport a blank stare, exposed by the bright flash of a camera. They seem like visual proof, tokens of having been thrown, kicked, punched, spat, cried, and vomited upon – so ultimately the epitome of abuse and trauma. But were Ant-Man, Teddy and Rabbit really just physical witnesses to something horrible that was inflicted upon them? It is apparent that they are more there to tell a more complicated story.

Because on the other hand, these individual portraits still appeared to me like a collection of mug shots: seemingly innocent cuddly toys depicted as perpetrators on the stand in an almost accusatory manner. From that perspective they seemed to suddenly stand for shame and guilt – but how could stuffed animals be guilty of anything? Their images are physically enclosed, separate from each other, and kept in tyrannical order by a strict, linear picture frame – did they stand for something that was kept secret within the walls of a children’s nursery? But why were they augmented or maybe even contrasted by a further mug shot: one of a grim-looking male adult? Was he depicted as the abuser, with dark circles under his eyes, in a buttoned-up beige dress shirt? Or a prison guard?

That’s exactly what made Mike Kelley’s artwork so memorable, all of these questions and discrepancies…

There was more artwork on display in the exhibition including soft toys and I realized, how tempting it was to read soft toys as relics of an innocent and happy childhood. Moreover, to view in general, in society, nurseries as safe spaces. Childhoods are happy and parents loving – or not? But this is the very reason why so many moral conflicts occur when these ideas are challenged: Any notion that disrupts these stereotypes and clichés is easier being denied, which is why at that point in my life, just intuitively, I found his work compelling and courageous. Ultimately, for the very reason, parental abuse is so crazy-making.

Looking at his body of work, one may interpret his works of art, like those described above, as a result of trauma, translated into the many often disturbing, but clever images he produced. But this wasn’t what I was interested in asking. I didn’t need to know whether this ensemble of tatty, abused-looking creatures gave the observer biographical information about the artist. Nor was I really interested in speculating about why precisely he killed himself. The topics were evident. That was enough.

Standing there this afternoon, on a hot afternoon in September 2022, taking pictures of the mural, I realized that since his death in 2012, a whole decade had gone by. The mural also made it apparent that an artist (I have yet to find out who it is) revered Kelley enough to create a large double portrait on a prominent street corner. But also, that not only Kelley was deeply ingrained in the city’s cultural fabric but I was too. I had memories, whether of a painful or a joyful nature, which connected me socially, geographically, and emotionally to this schizophrenic city.

I suddenly realized why I had felt so compelled to attend his make-shift memorial in 2012.

I had felt on that strange, dimly-lit evening of his impromptu memorial that he deserved my tribute because I admired his courage to touch upon subjects that are still – decades later – socially somewhat taboo and sadly, therefore, for many unresolved. As children, we rarely have an ally when being abused or mistreated, ignored, or neglected by a parent. Moreover, until we heal we only too often put ourselves on the stand and take mug shots of ourselves – since, for any child, the reality of having an abusive parent is too painful and can threaten basic survival needs. Mike Kelley epitomized these complicated and highly problematic emotions.