Rapid technological development has led to a constant flood of visual and acoustic bits and bites – emails, text messages and Facebook updates. For most of us it has become a habit to react, one that often leaves us frazzled and detached. Single-tasking has become a luxury in the 21st century. To sit down and simply read a poem, so to only focus on one individual piece of work, can feel as if we’re not doing enough, or even wasting time. Besides, especially poetry can seem very inaccessible. It is not easily consumed; it does not offer clear-cut outlines, neat bullet points or answers to your most urgent questions in life. Poetry demands from both the writer and reader attentiveness and reflection, moreover, intellectual and emotional engagement.

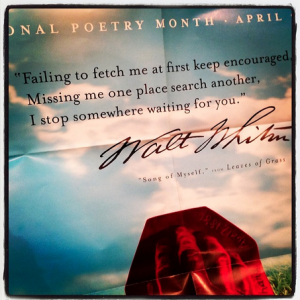

I am writing this on April the 2nd, two days into National Poetry Month 2014. First launched in 1996 with the support of the Academy of American Poets, the month of April was declared National Poetry Month.[1] Some literati like to argue that the celebration of poetry should be a daily and not an annual event confined to a month. But this is not the discussion I want to engage in at this point. I am taking this event as an opportunity to reflect upon the role poetry can play in our lives.

Anyone who engages in poetry – or in any kind of art form – is most likely both curious and highly sensitive. Our attention is usually not drawn towards the general or the spectacular but towards the singular, with its nuances and notions, shadows and shades. Those of us who write poetry must often follow the invisible; we hunt after illusions, traces, and wisps of things. With the patience of field archaeologists we excavate vague impressions we are sometimes barely able to grasp, often agonizing over every word and phrase. Our reward is when this „tantalizing vagueness“, like Robert Frost called it, takes on forms and meanings that lie beyond our expectations, like hidden little gems waiting to be uncovered.[2] Aristotle wrote of poetry as, „a kind of thing that might be“, in contrast to history as something that was.[3]

Both reading and writing poetry demands of us opposing virtues; we have to be both intuitive and logical, heart and head strong, playful and disciplined. Poetry teaches us an awareness of the wonders of the world, of mankind and of language. Through poetry we take in others, their universe, their views, anxieties, beliefs and emotions – snapshots which can even mirror our own.

Poetry „cannot reduce life, with all its pain, horror, suffering and ecstasy, to a unified tonality of boredom or complaint“[4]. Poetry facilitates reflection and compassion. It connects us not only with others but also to ourselves. My maternal grandmother suffered from Alzheimer’s disease. It was painful so see how every day she seemed to be vanishing a little bit more into this inescapable thick fog, like a ship with once billowing sails, now deflated and torn, lost at sea. But even when she couldn’t recognize most family members anymore, she could still recite poems from her youth. The poetry she loved and had mostly learned by heart still enabled contact with her own identity, with herself.

[1] The Russian poet Joseph Brodsky, who with the help of W. H. Auden was living in American exile, had declaimed that poetry should be available everywhere. In 1993 together with the student Andrew Carroll he founded the non-profit organization American Poetry and Literacy (APL). Three years later the movement was flourishing and over 125,000 books of poetry had been distributed for free.

[2] See my blog post “The Pomegranate – On Finding Poetry“.

[3] “The distinction between historian and poet is not in the one writing prose and the other verse… the one describes the thing that has been, and the other a kind of thing that might be. Hence poetry is something more philosophic and of graver import than history, since its statements are of the nature rather of universals, whereas those of history are singulars.” ~ Aristotle, On Poetics.

[4] Czeslaw Milosz, A Book Of Luminous Things. An International Anthology of Poetry, San Diego, New York, London 1996, p. XVI.